Blog.

The Unbearable Lightness of a Counterfeit AC/DC Ticket

FEBRUARY 11, 2009

In November, I roped my pal Clive Thompson into joining me for one of the two AC/DC shows at Madison Square Garden. Though I wasn’t a huge AC/DC fan back when I was a guitar-playing, classic-rocking adolescent, I’ve become sort of obsessed with them in the last few years. Their rhythm section is one of the tightest, most rocking ever—viva Malcolm Young!—and their devotion to pure rock form hasn’t wavered in 35 years.

Their new album, Black Ice, is pretty fine, and the lead track, “Rock ’n’ Roll Train,” is one of their best since the early-’80s glory years with producer Mutt Lange, who focused the band’s raw power and shaped the rhythm section into an incredibly tight, earth-shaking combo.

Clive and I didn’t have tickets to the show, which was sold out, and neither of us wanted to pay face value, about $90 each. So we planned to try our luck with the scalpers outside. If we failed, we’d just go drink beer somewhere in the neighborhood. We showed up outside the arena an hour after the doors opened, figuring that scalpers would be eager to get rid of any unsold tickets by then. Our price goal: $60 each. We didn’t know if this was realistic, but we weren’t too worried about it, because drinking beer was a pretty good backup option.

And that’s how we came to buy two counterfeit tickets. First I’ll tell the story of how and why we bought them, and then I’ll show you the ticket.

Neither Clive nor I had been to an arena-rock show in years. We knew we’d have to be on the lookout for ripoffs and scams, but we weren’t sure we’d be able to detect a professionally forged ticket. For all we knew, recent advances in printing technologies had led to a mishmash of ticket styles, with different appearances generated by different printing systems: at the arena, at a record store, at Ticketmaster outlets, and so forth. Had increased computerization led to greater standardization of ticket appearance, or less? We didn’t know. We also wondered whether scalpers had enough design talent to forge tickets convincingly.

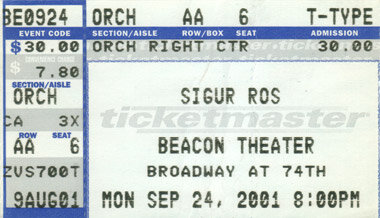

I’ve always been a saver of concert ephemera, and my computer-printed tickets for big shows have looked more or less the same since the mid-’80s. Here are a few ancient and recent examples from my collection. Check out the price of the Yes ticket—$12.50!

Outside the AC/DC show, extreme vigilance initially wasn’t necessary. The first scalper I talked to flashed a couple of tickets that seemed utterly fake. The card stock was oddly sized, and light blue, and the fonts and design were off. I wasn’t able to study the them closely, but they didn’t remotely resemble any arena-rock tickets I’d ever seen. So I said thanks and walked away, without being completely sure they were fake. Would someone really try to sell fake tickets without bothering to design them so they looked sort of real? (Within the hour, it became clear that the answer is yes.)

Eventually Clive and I approached another scalper, who offered us two tickets for something like $150 each. When we said we were thinking more like $50 each, he didn’t flinch, which was an obvious red flag. But we figured, Hey, maybe he just wants to get rid of them and go home; at this point it was about 9:30, and it wouldn’t be long before AC/DC took the stage. The scalper handed us the tickets and let us study them for a minute or two, and they did look sort of real. There wasn’t much light where we were standing, and we could see that the font wasn’t the dot-matrix typeface we were used to seeing on Ticketmaster’s tickets. Other than that, the scalper’s tickets looked fairly similar to the ones I’ve bought over the last 25 years or so. The font difference could have been due to nonstandardized printing technologies.

Nevertheless, Clive and I had enough doubts that we handed back the tickets and walked away. We spent a few minutes talking about whether we wanted to risk getting ripped off, and eventually we agreed that it was worth risking 60 bucks each for a chance to get into the show. I said that the worst thing that could happen would be that I’d have something funny (and design-related) to post on Panopticist.

We found the guy again, studied the tickets for another minute or two, steadied our resolve, then handed the scalper $60 each. He walked away, and we walked into the arena.

As we approached the turnstiles, I figured that if the tickets were fake, the ticket taker would probably have to study them a bit to figure it out. But…

She took one glance at mine and said, “I’m sorry, sir, this is fake.” She and her co-workers clearly felt sorry for us, but we just laughed and said we had a feeling they were probably fake. I asked her to show me a real ticket, and sure enough, it looked like all the others I’ve bought over the years. She said there aren’t other styles.

Below is the front of the ticket. In the clear light of day, when the details are easy to study, this thing is obviously, laughably a forgery:

The main giveaway isn’t the use of Arial throughout; corporate behemoths like Ticketmaster have never been shy about using that awful typeface. No, the forgery is obvious because the typesetting is so amateurish. There’s an errant space in the Live Nation URL; an impossible slash in the AC/DC URL; and a stupid comma in “NOV, 13 2008,” to name just a few things.

For comparison, here’s a Ticketmaster ticket from a 2006 Flaming Lips show I went to:

Here’s the back of the counterfeit ticket, with the back of the Flaming Lips ticket underneath for comparison:

Once Clive and I knew we wouldn’t be getting into the show, we walked to a bar on Seventh Avenue and drank beer and laughed.

This all raises an obvious question: Couldn’t a halfway talented typographer/printer make a killing with carefully forged concert tickets? It wouldn’t be hard to do it a lot better than these guys. And they’re clearly making some money that way, or they wouldn’t be out there at all. Good forgeries probably wouldn’t even be detectable by the ticket takers at the door, let alone by schlumps on the street.